This report is part of the “Open Web Apocalypse” series – a four-part deep dive into how Google’s recent actions have shaken the foundations of the independent web. From the unHelpful Content Update to the Great Content Heist, each chapter unpacks a different facet of this unraveling ecosystem.

The entire series was written by asking ChatGPT DeepSearch to trace, compile, and connect the key events, patterns, and consequences that unfolded over the past 18 months—across scattered sources, insider accounts, and SEO carnage. The goal? To make sense of what’s really happening to independent content creators… and where this is all heading.

Table of Contents

- 1. Training on Publishers’ Content: From “Helpful” to Exploited

- 2. Google’s Shift from Search Engine to Answer Engine

- 3. The Flawed Opt-Out Model for AI Usage

- 4. Chegg vs. Google: A Case Study in AI’s Competitive Harm

- 5. The Expansion of Sponsored Placements on Google

- 6. Click Redistribution and Google’s Revenue Growth

- 7. The Future of the Open Web at Stake

- 8. Antitrust Implications and Calls for Scrutiny

Google’s evolution from a neutral search engine into an AI-driven “answer engine” is reshaping the web’s landscape – and not for the better. As Google increasingly answers users’ queries directly on its own pages using AI summaries, independent publishers find themselves cut out of the equation. The very open-web content that Google’s algorithms once indexed (and sometimes penalized) is now being repackaged into AI-generated answers with little credit or traffic flowing back to the original creators. This whitepaper-style report examines how Google’s AI strategy, algorithm updates, and advertising tactics reinforce its market dominance at the expense of publishers, user choice, and a diverse open web. It highlights structural imbalances and calls for scrutiny to ensure a fair digital information ecosystem.

Training on Publishers’ Content: From “Helpful” to Exploited

Google’s new AI tools – from Search Generative Experience overviews to the Bard chatbot – have been trained on vast swathes of web content scraped from the open internet (theverge.com). This corpus undoubtedly includes content from countless independent publishers and websites. Ironically, some of these very sites were downranked by Google’s own Helpful Content Update for being “unhelpful” (i.e. content created primarily to rank in search) (mariehaynes.com). In August 2022, Google introduced the Helpful Content system to demote content “that exists just for SEO purposes” (mariehaynes.com). Yet now Google’s generative AI freely draws upon all web content – including those same articles deemed unworthy of search prominence – to produce answers for users.

The result is a profound irony: content judged “not helpful” enough to rank can still be regurgitated by Google’s AI answer engine, only now with Google as the intermediary. Publishers receive none of the credit, traffic, or consent for this reuse. A 2024 investigation by Press Gazette underscores this imbalance. It found Google’s AI Overview summaries are often essentially “an exercise in taking publisher content with little value given in return” (pressgazette.co.uk). In cases where Google provides an AI-generated answer drawn from a publisher’s journalism, the publisher’s own link is pushed far down the page – potentially reducing their traffic by 85% if the AI answer replaces the top result (pressgazette.co.uk). All the while, the information originated with the publisher is being served to users in Google’s walled garden, with no compensation or even a clear attribution in many cases.

This practice raises fundamental questions of fairness. Google’s AI was built on the rich trove of openly accessible content that web publishers created. But now that same company can declare some of those sites unworthy of visibility (via algorithm updates) while still profiting from their content behind the scenes. Even copyrighted materials have been swept into Google’s training data. In France, the competition authority fined Google €250 million after finding the company used news publishers’ articles to train its Bard/Gemini AI without permission or any opt-out in place (cio.com) (cio.com). In short, Google’s AI appetite is built on the labor of others, yet those original creators increasingly see no benefit – a dynamic that independent bloggers, niche experts, and small news outlets find deeply troubling.

Google’s Shift from Search Engine to Answer Engine

Over the past few years, Google’s search results page (SERP) has transformed from a gateway to websites into a destination itself – an “answer engine” where users can often get what they need without ever leaving Google. With features like Featured Snippets (quick answers), Knowledge Panels, and now AI-generated “AI Overviews” at the top of results, Google is keeping users on its platform by directly providing answers. As one observer bluntly summarized: “They are no longer a search engine to find websites, they are an answer engine.” (reddit.com). The design is deliberate. Internal voices note that Google sees sending traffic outward as counter to its goals – a former Google executive even admitted that “Giving traffic to publisher sites is kind of a necessary evil. The main thing they’re trying to do is get people to consume Google services.” (“Because Google’s AI is trained on the web, its answers are a kind of remixed version of the web itself, while also distorting the economy that gave rise to the modern internet by potentially cutting the sites out of the equation entirely.” ~ Davey Alba : r/ArtistHate) In other words, Google’s incentive is to satisfy the query on Google’s page itself whenever possible, rather than risk the user clicking away.

The rollout of the Search Generative Experience in 2023–2024 exemplifies this strategy. Google’s AI Overview answers now appear for a substantial portion of queries – nearly 24% of news-related searches in one study – effectively displacing the traditional organic links that used to get those clicks (pressgazette.co.uk) (pressgazette.co.uk). When an AI summary is shown, the top organic result (often a publisher’s page) gets pushed down by roughly 980 pixels – equivalent to moving from rank #1 to about rank #5 in visibility (pressgazette.co.uk). This means a user often has to scroll past Google’s answer box and perhaps other Google-provided info before even seeing a normal link. Unsurprisingly, click-through rates on those organic results plummet. Publishers that used to enjoy ~40% of clicks at the top position may see as little as 5% now – an 85% drop in potential traffic if an AI answer intervenes (pressgazette.co.uk).

For independent publishers, the implications are dire. Fewer people clicking out to their sites means fewer ad impressions, subscriptions, or engagements on their own content. The diversity of knowledge available to the public could suffer as a result. If users only see the one-size-fits-all summary that Google’s AI provides, they may miss out on alternative perspectives or deeper nuance found on individual websites. Knowledge diversity is inherently reduced when a single platform mediates answers to millions of questions, often drawing on the same homogenized training data. As tech journalist Davey Alba put it, Google’s AI answers are essentially a “remixed version of the web itself,” delivered in a way that risks “cutting the sites out of the equation entirely.” (“Because Google’s AI is trained on the web, its answers are a kind of remixed version of the web itself, while also distorting the economy that gave rise to the modern internet by potentially cutting the sites out of the equation entirely.” ~ Davey Alba : r/ArtistHate) This “remix” may be convenient, but it comes at the cost of the open web’s richness and pluralism.

Equally worrying is what this trend means for the long-term viability of high-quality content creation. Google itself has touted that it is the largest referrer of traffic to the web – driving nearly two-thirds of external traffic for top sites (androidcentral.com). If that referral firehose slows to a trickle, many publishers will struggle to survive. Users might not notice immediately – after all, Google is giving them quick answers. But over time, the pool of new knowledge and journalism shrinks if those who produce it can’t sustain their operations. Even Google’s own promotional AI overview has noted the stakes: “Google is the biggest referrer of web traffic on the internet — and it really isn’t close” (androidcentral.com). With great power as the web’s gateway comes great responsibility; yet Google’s recent moves suggest it is prioritizing keeping users in its ecosystem over the health of the broader information commons.

The Flawed Opt-Out Model for AI Usage

In response to growing pressure, Google and other AI providers have introduced mechanisms ostensibly allowing publishers to opt out of having their content used for AI training or answers. In late 2023, Google announced a new flag called Google-Extended that sites can add to their robots.txt, telling Google’s crawlers not to include that site’s content in training data for models like Bard (while still indexing it for search) (theverge.com). On paper, this sounds like giving publishers a choice. In practice, it’s a band-aid on a much larger wound – and one applied only after terabytes of data have already been consumed by Google’s AI.

The reality is that most content has already been ingested and used to train models retroactively, long before opt-out was offered. Google confirmed in mid-2023 that Bard was trained on publicly available web data (theverge.com), which implies that unless a site had been blocking all Google crawling (a self-defeating move), its content likely ended up in the training mix. For many small publishers, the new opt-out toggle comes far too late – the horse has left the barn. Moreover, using the opt-out going forward puts them in a commercial bind. Blocking Google’s AI crawler might protect their content from being synthesized into Google’s answers, but it could also hurt their presence in Google Search. As The Verge noted, websites can’t practically block Google’s main crawlers or else “they won’t get indexed in search” (theverge.com). In other words, telling Google “don’t use my content for AI” could have unintended consequences if it also means Google Search begins to marginalize that site (since Google might treat excluded content as less available or relevant).

The opt-out dilemma especially hurts smaller publishers who rely on Google for discovery. Major outlets like The New York Times or CNN might be able to negotiate or even legally challenge AI usage of their content (indeed, some have blocked OpenAI’s crawler and reportedly considered lawsuits), but a solo blogger or niche forum has no such leverage. They face a Catch-22: allow Google to freely mine and summarize your content without compensation, or disappear from the primary channel (Google Search) through which readers find anything. As France’s regulator found, Google even failed to provide news publishers with a functional opt-out before using their articles in AI, breaching commitments to negotiate in good faith (cio.com). The current “solutions” put forth by tech companies feel insufficient – a token checkbox that does little to restore balance or reward content creators.

For an opt-out regime to be fair, it would need to be coupled with real incentives or alternatives. Perhaps regulators could require that content used to train AI or to generate answers must involve some form of licensing or compensation, the way music streaming had to negotiate with record labels. Right now we effectively have involuntary, uncompensated servitude of content: publishers’ works fuel the AI answers that increasingly divert traffic away from those same publishers. That dynamic is not sustainable if we value a vibrant open web.

Chegg vs. Google: A Case Study in AI’s Competitive Harm

Nothing illustrates the potential harms of Google’s AI answer approach better than the recent legal fight between Chegg and Google. Chegg, a publicly traded education technology company known for its textbook solutions and study help content, saw a precipitous decline in user traffic and business metrics in 2023. The culprit, in their view, was Google’s AI Overview feature which started providing detailed answers to student queries directly on the search page – answers often derived from Chegg’s own proprietary content.

In early 2025, Chegg took the dramatic step of filing a complaint against Google, alleging that the new AI-driven results have “materially impacted our… revenue, and employees” (searchengineland.com) (searchengineland.com). The company stated that if not for Google’s launch of AI Overviews (AIO), it would not be in such dire straits requiring strategic alternatives. Chegg’s complaint argues that Google’s AI is essentially using Chegg’s content to retain traffic on Google’s platform, thereby “blocking” that traffic from ever reaching Chegg (searchengineland.com). In other words, students who previously might click a Chegg link for homework help now get a synthesized answer on Google – one informed by Chegg’s materials – and thus have little incentive to visit Chegg’s site or subscribe to its services.

The impact on Chegg’s business has been severe. By late 2024, Chegg’s market value plummeted and its revenues were down significantly (searchengineland.com). The company even hired bankers to explore a sale or other strategic moves, highlighting how existential the threat had become (searchengineland.com). Here we have a concrete example of Google’s dual role as both information intermediary and now a direct competitor to specialized information providers. Chegg invested for years in creating a vast library of educational answers (some of which sit behind a paywall), only to have Google effectively scrape and repackage those answers for free in search results. From an intellectual property standpoint, this raises serious questions – Chegg’s content is proprietary. From a competition standpoint, it looks like Google leveraging its dominance in general search to invade a vertical (study help) and siphon away a competitor’s users by offering a clone of their product (AI-derived answers).

Chegg’s lawsuit may be the first major salvo, but it likely won’t be the last. Other companies that provide high-value content – think of recipe websites, travel guides, code repositories, and beyond – are surely watching. If Google’s AI can summarize and present the core answers from any site, the entire ad-supported web model is at risk. Notably, Google claims that its AI answers are intended to help users and that publishers will still get clicks (or that traffic is just being “redistributed”). But publishers strongly disagree: third-party data shows click-through rates from AI overviews are abysmal (seroundtable.com) (seroundtable.com), and now Chegg’s drastic action underscores that real revenues are being lost. This case also spotlights the copyright angle: Chegg says Google did not have license to use its content this way, raising the issue of whether AI scraping violates content owners’ rights. The outcome of Chegg v. Google could set important precedents for how far platforms can go in using others’ content to power AI features – and whether such behavior might be deemed anti-competitive. It’s a classic example of a monopolist (Google) allegedly exploiting its dominance (in search distribution) to undermine a smaller competitor by appropriating their product.

The Expansion of Sponsored Placements on Google

While Google’s organic search is being squeezed by AI answers from above, it’s also being crowded out from the top and bottom by an ever-growing array of sponsored placements. Over the years, Google has steadily increased the number, size, and prominence of paid results on the SERP. Once upon a time, Google showed a modest three text ads in a column and ten “blue link” results on a clean white page. That era is long gone. Today’s Google results are a dense tapestry of ads, shopping carousels, map packs, and other Google-served features, with organic links often pushed below the fold on many screens.

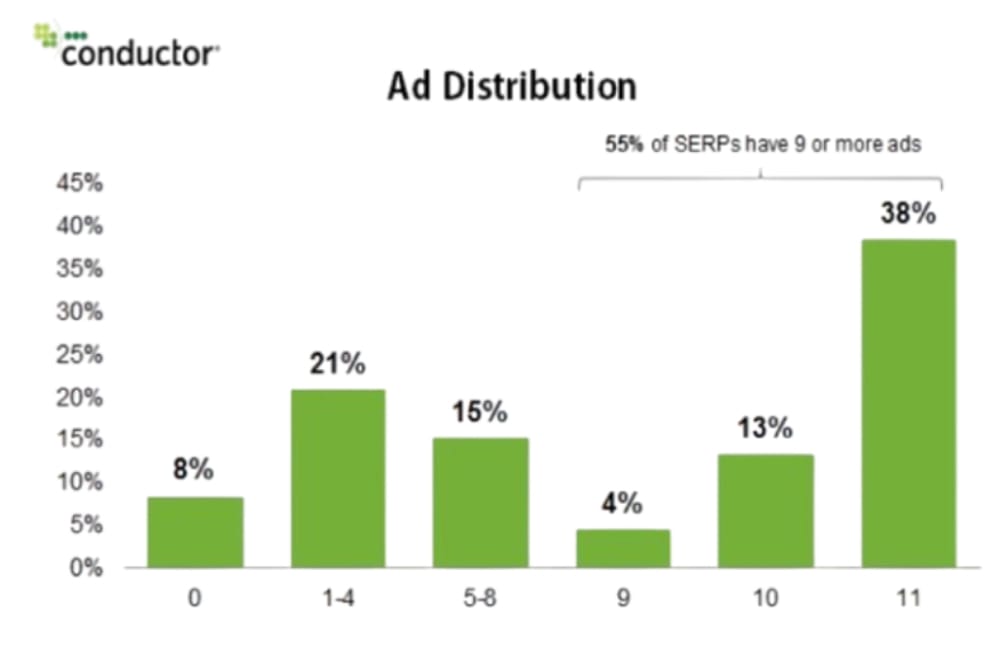

A recent analysis found that Google now shows nine or more ads on over half* of search results pages (riseatseven.com). In fact, about 55% of Google SERPs contained 9+ ads, according to a Conductor study, and a full 13% of SERPs had 10 ads while a whopping 38% had 11 ads* (riseatseven.com) (riseatseven.com). These ads can include up to four paid search text ads at the very top, several ads at the bottom, plus shopping ads or local service ads in between. The practical impact is that a user’s entire initial view might be advertising material. For example, on a commercially valuable query like “best credit cards,” one might see a headline “Sponsored” carousel, a few text ads, and maybe a comparison box – all before the first unpaid result appears. The “ten blue links”** of organic results are now often an afterthought.

Not only has the quantity of ads increased, but Google has made them more visually engaging and more blended with organic content. Product listing ads show images and prices (enticing clicks), local ads are pinned on maps, and even text ads now have site links and extensions that make them occupy more screen real estate. Google has also periodically altered ad labeling (from colored backgrounds to subtle “Ad” tags) in ways that critics say make them less distinguishable from organic results. The net effect is that sponsored content dominates the user’s attention. Independent websites that rely on ranking high must not only compete with each other, but also literally compete for screen space against Google’s own ad inventory.

Why would Google flood its results with more ads? The answer is simple: revenue. Google earns the majority of its $200+ billion annual ad revenue from search advertising. By inserting more ad units and pushing them in front of users, Google increases the chances of clicks on paid results, which directly boosts its income. Even as overall search query growth moderates, Google has managed to keep revenue climbing by turning the dials of monetization. In late 2023, Google quietly rolled out larger ad formats on mobile and began mixing in more sponsored snippets. Not coincidentally, its search ad revenues continued to grow, whereas publishers’ share of clicks shrank. This imbalance means Google’s profit engine hums along even as the open web’s visibility is dimmed under sponsored content.

Click Redistribution and Google’s Revenue Growth

Google’s near-total dominance of the search market (around 90% share globally) means it faces one main constraint on revenue: there are only so many searches performed in a day. To keep growing financially, Google must extract more value from each search rather than rely on significant user growth. This reality has driven a strategy of redistributing clicks – away from external, unmonetized results and toward Google’s own monetized or controlled surfaces. In essence, every click that a user doesn’t make to an organic publisher site is potentially a click they might make on an ad or within a Google property. From Google’s perspective, keeping users on Google pages longer and more often is simply good business.

The numbers bear this out. In 2024, U.S. search ad spending rose by 17% year-over-year even though the number of clicks (searches resulting in a click) grew only 4% (searchengineland.com). How can revenue jump 17% on just 4% more clicks? By charging more per click (CPC) and showing more ads per search. Indeed, the average cost-per-click for Google Search ads jumped ~13% in that period (searchengineland.com) (searchengineland.com) – indicating advertisers are paying more, likely because those ads are getting prime exposure. Over the past five years, Google’s search ad CPCs are up 40-50% for many industries (searchengineland.com). This is the direct outcome of a “pay to play” environment where organic prominence is harder, so businesses feel pressured to bid on ads to get visibility. As Google gives itself more ad inventory (and as its algorithms sometimes favor its own verticals like Shopping or Local), it can demand higher prices from advertisers for the privilege of remaining visible.

Beyond pure ads, Google has also funneled clicks into its own properties. For every search that might have led a user to, say, Wikipedia or a travel blog, Google tries to answer it via Google Maps, Google Flights, YouTube, or other products it owns – all of which have their own monetization (YouTube shows ads, Maps can promote sponsored locations, etc.). As of 2024, nearly 30% of all clicks on Google searches in the U.S. go to Google’s own properties (searchengineland.com). Only about 36% of clicks now go to the open web (non-Google sites), with the rest being zero-click or Google-internal clicks (searchengineland.com). That represents a massive redistribution of traffic over the past decade – effectively siphoning user engagement away from the broader web and into Google’s closed ecosystem.

This redistribution is not an accident; it’s by design. Internal documents from ongoing antitrust litigation revealed that Google executives have long discussed ways to integrate and highlight Google’s “universals” (images, shopping, local, etc.) and rich answers on the SERP to capture “corner clicks” that would otherwise go elsewhere. The more Google can solve a user’s whole query journey in-house – whether by an AI chat, a knowledge panel, or a map snippet – the fewer opportunities rivals or independent websites have to engage that user. In business terms, Google is maximizing per-query revenue. If a user looking for “best restaurants” sees a full Google-made list and map with sponsored entries, they might never visit the independent restaurant review blog that painstakingly curated a top-10 list. That blog loses a visitor (and ad impression), while Google gains a possible ad click or at least keeps the user in its realm for the next query.

Critically, this isn’t expanding the pie of user attention – it’s reallocating the same attention. We are still largely dealing with the same number of searches and eyeballs; Google is simply ensuring a greater share of each search benefits Google and not others. As one analysis pointed out, this becomes concerning when a dominant firm “expands into new verticals and essentially ‘takes over,’ leaving websites to fight for crumbs of organic search traffic” (searchengineland.com). That is exactly the state of affairs we’re approaching. Google’s revenue grows, not because it’s sending more traffic out (that could indirectly generate revenue via happier users clicking more often), but because it’s sending less traffic out and monetizing those withheld clicks itself.

For independent publishers and competitors, this dynamic is zero-sum and deeply unfair. Google’s dual role as the referee (search ranking algorithm) and a player (content provider, ad seller) means it can tilt the field to favor its own outcomes. Every additional dollar Google earns from an extra ad click might be coming directly out of a publisher’s pocket, as it represents a user who didn’t click the unpaid result. The company’s claim that AI overviews or new features “lead to more clicks” has not been substantiated with data – on the contrary, outside studies show precipitous drops in organic click-through when these features appear (seroundtable.com) (seroundtable.com). In practical terms, Google has redirected a torrent of traffic that once fueled the broader web and channeled it into its own funnels (ads, Google services), boosting its revenue on the backs of everyone else’s content and effort.

The Future of the Open Web at Stake

If current trends continue unchecked, the consequences for the open web are alarming. We could be headed toward a digital ecosystem where information is overwhelmingly filtered through a single corporate intermediary. In such a future, information diversity and content sustainability would suffer greatly. Fewer independent websites will be able to survive when they can’t get traffic or revenue. Some will pivot to serving content directly on platforms (for instance, publishing within Google’s walled garden) or give up entirely. The voices that remain might be only the largest, most established sources – and even they might find themselves strong-armed into unfavorable terms just to be included in AI answers or other aggregated results.

One immediate impact would be on journalism and quality information production. News organizations, big and small, depend heavily on Google for discovery. It’s estimated that Google Search drives about one-third of traffic to news publishers (pressgazette.co.uk). Cut that by half or more (via AI answers and zero-click results) and many outlets will face budget crunches. Local news, which is already endangered, could virtually disappear if people stop clicking local articles and just read AI-generated summaries of events. Investigative and long-form journalism might be seen as even less cost-effective if quick AI blips steal the audience. We risk a decline in the depth and accountability of information – a scenario where the loudest or most centrally aggregated content wins over thoughtful, niche analysis. Moreover, if AI models are trained on a shrinking corpus (because new high-quality content isn’t being produced or is locked away), the models themselves could stagnate and amplify biases, errors, or outdated knowledge.

User trust in information may also erode in this landscape. Google’s own AI answers have already shown they can be flawed – early examples of SGE provided “dangerous and wrong answers” in sensitive areas (searchengineland.com). When Google pulled back some of those features, it acknowledged the need for quality control. But if users become habituated to getting answers without context or source, they may not know when to question a result. A generative AI can state a falsehood with the same confident tone it states a fact. Without the open web’s array of sources to click through (and the habit of cross-verifying information by reading multiple sites), misinformation can potentially spread more easily. In a healthy open web, a user might read a claim on one site, then see a different perspective or correction on another. In a closed answer engine, the first answer might also be the last, giving a single entity tremendous power to shape narratives.

Importantly, the dominance Google holds is already officially recognized. In October 2024, U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta ruled in a landmark antitrust case that “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly.” (theverge.com) He found that Google had illegally maintained monopoly power in general search services (and search advertising) in violation of antitrust laws (theverge.com). This finding underscores that Google has no true competitors in search – a reality that magnifies every issue discussed here. When a company that effectively controls the gateway to information also starts unilaterally determining how information is presented (AI answers) and whose content gets priority or gets used without license, it raises red flags about the long-term health of the internet. Monopolies tend to stifle innovation; a Google that faces no competition has little incentive to balance its own profit motives with the needs of the ecosystem. The open web flourished under a more decentralized model, where thousands of sites could compete for attention on relatively equal footing in search results. That equilibrium is now disturbed.

The trajectory we’re on could lead to an internet that is “open” in name but not in practice. Imagine a student in 2027 researching a topic: instead of finding a trove of independent blogs, forums, and news sources, they get a single aggregated answer, maybe a Wikipedia blurb, and a handful of corporate sites that have paid for visibility or struck deals with the platform. The serendipity of discovering a new insightful blog or a community forum could vanish. The “long tail” of content – those niche sites that serve specific interests or local communities – might wither due to lack of traffic. This would be a profound loss for innovation and education. Many of today’s greatest web platforms and ideas (including Google itself, which started as an academic project) arose in an open environment where the best information could bubble up organically. If that environment is compromised, we might never see the next Wikipedia, the next Stack Overflow, or the next independent media outlet gain traction.

Antitrust Implications and Calls for Scrutiny

The challenges posed by Google’s AI-driven transformation are not just a matter of tech industry squabbles; they strike at the heart of fair competition, copyright, and the public interest. Regulators and lawmakers are increasingly faced with a compelling question: Does Google’s current behavior warrant new forms of oversight or intervention? The evidence suggests yes. When a dominant firm uses unlicensed content from others to enhance its own platform and simultaneously undermines those very content producers by cutting off their traffic, it presents a case for regulatory scrutiny on multiple fronts.

First, there is the antitrust dimension. Google’s leveraging of its search monopoly to favor its own services and answers can be seen as an extension of the self-preferencing behavior that antitrust law is concerned with. The DOJ’s lawsuit (and Judge Mehta’s findings) already established that Google maintained its monopoly through exclusionary agreements (like default search deals). But what about maintaining monopoly through product design? By integrating AI answers that use third-party content without compensation, Google may be entrenching its dominance in a way that regulators haven’t fully grappled with yet. It’s effectively foreclosing the market for organic referral traffic – a market that countless businesses rely on – to shore up its position as the one-stop shop for answers. Regulators could consider whether this behavior constitutes a form of anti-competitive conduct (for example, “exploiting a bottleneck” or essential facility without fair dealing). The Chegg case, if it proceeds, might surface evidence of deliberate tactics by Google to eliminate the perceived need for visiting other sites in certain verticals, which could bolster claims of monopolistic abuse.

Secondly, there’s the issue of intellectual property and fair use. The mass ingestion of web content to train AI (without consent) exists in a legal gray area. Some lawsuits (outside of Google) have already been filed against AI companies for copyright infringement via training data. Google, due to its size, has thus far avoided a direct broad-based publisher lawsuit on this front – but Chegg’s complaint edges into that territory, and others may follow. Lawmakers might need to clarify whether using content to generate an answer (which might deter someone from clicking the source) should still require attribution or licensing. Traditional copyright law didn’t anticipate AI that can produce derivative summaries on the fly, so new frameworks might be needed to protect original content creators. If Google will not voluntarily share the spoils of its AI features (through traffic or revenue share), perhaps regulations forcing transparency and compensation (similar to how radio pays song royalties) should be on the table.

Thirdly, consumer protection and transparency are concerns. Users have a right to know where information is coming from and to have the option to dig deeper. One could argue that Google’s interface should more prominently credit sources for AI answers or offer easier ways to visit the underlying sources. Right now, Google’s AI overviews often cite sources in small print or footnotes (and sometimes not at all, if the info is deemed common knowledge). Mandating clear source links or even a requirement that any AI-generated summary be accompanied by multiple source options could at least funnel some traffic back to publishers and increase transparency. Regulators in the EU and elsewhere are already discussing AI transparency in other contexts; search might need its own set of rules to ensure it doesn’t become a black box of aggregated info.

Finally, the broader balance of the digital ecosystem is at stake. Policymakers who care about a competitive internet should view Google’s current trajectory with alarm. It is entirely possible that without intervention, we’ll see a further consolidation of power where Google’s position not only as a gateway but as a content arbiter is unassailable. This could discourage startups – why build a new niche content site if Google might simply absorb your content and deny you traffic? It could also force existing publishers into dependent relationships, where they either have to optimize for Google’s AI (in hopes of being one of the few cited sources) or pay Google for visibility (through ads or inclusion fees), reinforcing a cycle where Google wins either way. Such a scenario is reminiscent of past monopolies that taxed an entire industry. Here, Google would be taxing the information industry – skimming the value of all content while dictating terms to those who produce it.

In conclusion, it’s time to reassert the importance of the open web and fair competition. Google’s innovations in AI and search are impressive, but they should not come at the cost of the ecosystem that nourished Google’s rise. Small publishers, journalists, educators, and innovators have valid concerns that deserve action. Ensuring a level playing field may involve antitrust enforcement (as the DOJ case is pursuing), but also potentially new legislation tailored to the age of AI-driven platforms. This could mean rules around data sharing, requirements for fair revenue splits when AI outputs rely on others’ content, or even structural remedies if Google refuses to balance its dual role. The goal would not be to halt progress, but to ensure that progress is shared – that when AI provides value to users, it doesn’t undermine the very sources of that value.

As Judge Mehta’s ruling underscored, Google Search’s monopoly status is a reality (theverge.com). The onus is now on regulators and society to decide how to prevent that monopoly from choking off the open web. Defending the interests of small publishers and creators is not just altruism; it’s protecting the future diversity and reliability of information for all of us. The web’s greatest strength has always been the multitude of voices and sites that compose it. We must not let that be reduced to a single voice – even if it speaks with the synthesised eloquence of an AI – answering everything from on high. The time to act is now, to ensure Google’s evolution does not become the open web’s demise, but rather that we find a new equilibrium where innovation can thrive alongside a fair and open digital information ecosystem.

Sources: Google and industry reports, including Press Gazette on AI Overviews (androidcentral.com) (androidcentral.com), The Verge on Google’s monopoly ruling (theverge.com), and multiple expert analyses and studies as cited above.